New research sheds light on the precise daily cycles of cluster headaches and the surprising circadian connections of migraines

For people living with either cluster headaches or migraines, the daily disruption and pain caused by these headaches can be debilitating. A meta-analysis published in Neurology suggests that the onset patterns of cluster and migraine headaches are associated with the circadian system, which regulates the sleep-wake cycle, impacting these headaches’ occurrence time. Researchers examined available studies on both types of headaches that involved the circadian system, paying attention to the time of day and year of occurrence. They assessed studies on the presence of hormones like melatonin and cortisol, which are tied to the circadian system.

“Cluster headaches are well known among specialists ‘to have a precise daily cycle,” said lead study author Mark Joseph Burish, MD, PhD, of the University of Texas Health Science Center at Houston, adding that they weren’t surprised to find this connection with the circadian system. However, the migraine data surprised them the most. Dr. Burish explained, “Migraine, however, is not thought of as a highly circadian disease…We were surprised to find that migraine has such strong circadian connections—50% of patients report headaches at the same time of day, there are lower melatonin levels in patients, and there are genetic connections to circadian genes or genes controlled by the biological clock.”

Cluster headaches generally last for 30 to 90 minutes, while migraines can last a full day or even several days. One typically experiences one migraine at a time, while cluster headaches can clump together up to eight times in one day. Cluster headaches affect one side of the head, while migraines can be located all over the head. Genetic factors play a significant role in the presence of cluster headaches and migraines.

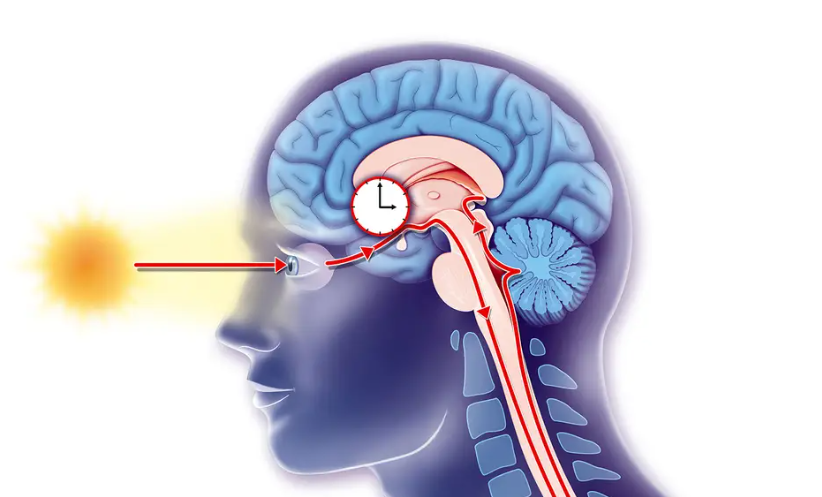

The research highlights how a circadian rhythm can regulate a phenomenon like a cluster headache. Dr. Rashmi Halker Singh, an associate professor of neurology at Mayo Clinic and a member of the Board of Directors of the American Headache Society, explained that sleep can be restorative for migraines, but many people who experience them unfortunately find a migraine waking them up in the middle of the night. This is not because of sleep but is due to circadian rhythms and the hypothalamus, a part of the brain that regulates sleep cycles, body temperature, and hunger.

Dr. Burish noted that acute medications are things taken during the headache to break it, while preventative medications are things taken regularly to reduce the frequency and intensity of headaches. Some preventive treatments for cluster headaches and migraines, like prednisone and melatonin, are known to alter the circadian clock, but not many other current medications can do the same. By better understanding the role of the circadian clock in headaches, there is potential to develop new drugs that can prevent headaches when they are most likely to occur.

However, the study has limitations. There is a lack of information on the factors that can influence a person’s circadian cycles, and the study’s sample size was relatively small. Future research could investigate the factors that affect circadian rhythms and how they could be managed to help reduce the frequency and severity of cluster and migraine headaches.