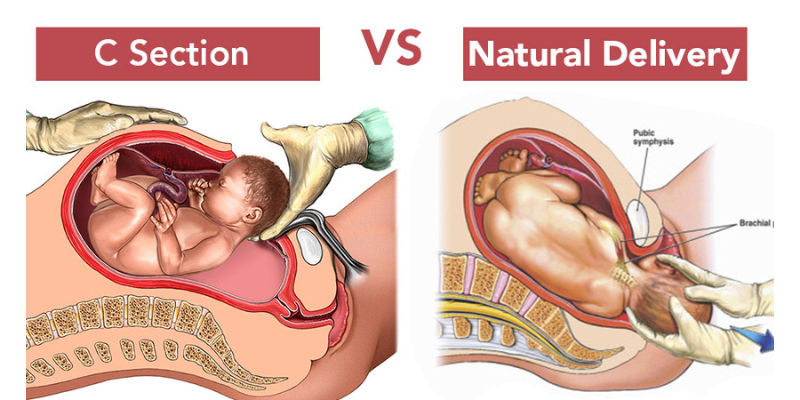

The debate surrounding the increasing rate of cesarean section (C-section) deliveries versus normal vaginal deliveries is a hot topic in the medical community. Cesarean sections have been rising over the years, with some countries reporting rates of up to 50% in some hospitals. The World Health Organization (WHO) has set a recommended upper limit of 15% of deliveries that should be by C-section. The increasing rate of C-sections has raised concerns about the potential risks and benefits to both the mother and the baby.

C-section deliveries are typically recommended in situations where there is a medical need or risk. Some reasons for a C-section may include a breech presentation, placenta previa, fetal distress, or a previous C-section. However, there is growing concern that many C-sections are being performed unnecessarily. In many cases, women may be encouraged to have a C-section for convenience, such as scheduling the delivery or avoiding the pain of labor.

One of the major concerns surrounding the increasing rate of C-sections is the potential risks to the mother. C-sections are major abdominal surgeries and carry risks such as infection, bleeding, and blood clots. Women who have had a C-section may also experience longer hospital stays and a longer recovery time. In addition, C-sections may increase the risk of future pregnancy complications such as placenta previa, uterine rupture, and preterm birth.

Another concern is the potential risks to the baby. While C-sections may be necessary in some cases, they can also increase the risk of breathing problems for the baby, particularly if the delivery is scheduled before the due date. Additionally, C-sections may interfere with the baby’s ability to establish breastfeeding, which can have long-term implications for the health of the baby.

Despite these concerns, there are some situations where a C-section may be the safest option for both the mother and the baby. For example, if the baby is in distress, a C-section may be necessary to deliver the baby quickly and safely. In other cases, a C-section may be recommended if the mother has a medical condition that makes a vaginal delivery risky.

There are several factors that have contributed to the increasing rate of C-sections. One factor is the rise in maternal age and the associated risks. Women who are over 35 years old may have a higher risk of complications during labor and delivery, which may make a C-section a safer option. Additionally, the increasing use of assisted reproductive technologies may also contribute to the rising rate of C-sections.

Another factor is the increase in obesity rates, which can increase the risk of complications during labor and delivery. Women who are overweight or obese may be more likely to have a C-section, particularly if they have other risk factors such as gestational diabetes or hypertension.

Finally, there is growing concern that the medicalization of childbirth has contributed to the rising rate of C-sections. In some cases, medical interventions such as induction of labor or the use of epidurals may increase the likelihood of a C-section. Additionally, the use of electronic fetal monitoring may lead to unnecessary interventions and ultimately a C-section.

While there are certainly situations where a C-section is the safest option, there is growing concern that many C-sections are being performed unnecessarily. This has led to calls for a more conservative approach to the use of C-sections and a greater emphasis on natural childbirth. One approach is to encourage women to try for a vaginal birth after a previous C-section (VBAC), which can be a safe option for many women.

There are several strategies that can be used to reduce the rate of C-sections. One strategy is to reduce the use of medical interventions such as induction of labor and electronic fetal monitoring. In addition, providing women with more information and support during pregnancy and labor can help them make informed decisions about their care and increase their confidence in their ability to give birth naturally.

Another strategy is to improve access to midwifery care and natural childbirth options. Midwives can provide personalized care and support during labor and delivery, which can help reduce the need for interventions and ultimately C-sections. This approach has been successful in some countries, such as the Netherlands, where midwifery care is the norm and the C-section rate is lower than in many other countries.

In addition, improving the quality of prenatal care can help identify and manage potential risk factors early in pregnancy, which can help reduce the need for a C-section later on. This can include providing education and support for healthy lifestyle choices, such as diet and exercise, and addressing any underlying medical conditions.

Finally, it is important to recognize that C-sections are a complex issue that requires a multifaceted approach. There are many factors that can contribute to the decision to perform a C-section, including medical, social, and cultural factors. It is important to understand and address these factors in order to provide safe and effective care for women and their babies.

In conclusion, the increasing rate of C-sections is a complex issue that requires careful consideration of the risks and benefits for both the mother and the baby. While there are certainly situations where a C-section is the safest option, there is growing concern that many C-sections are being performed unnecessarily. This has led to calls for a more conservative approach to the use of C-sections and a greater emphasis on natural childbirth. By implementing strategies such as reducing medical interventions, improving access to midwifery care, and improving the quality of prenatal care, it may be possible to reduce the rate of C-sections and provide safe and effective care for women and their babies.

Sources:

- World Health Organization. (2015). WHO statement on caesarean section rates. https://www.who.int/reproductivehealth/publications/maternal_perinatal_health/cs-statement/en/

- American College of Obstetricians and Gynecologists. (2021). Cesarean birth. https://www.acog.org/womens-health/faqs/cesarean-birth

- Healthline. (2021). C-section delivery. https://www.healthline.com/health/pregnancy/c-section-delivery

- National Institute of Child Health and Human Development. (2021). Cesarean delivery. https://www.nichd.nih.gov/health/topics/cesarean/Pages/default.aspx

- The Lancet. (2018). Too many caesarean sections? https://www.thelancet.com/journals/lancet/article/PIIS0140-6736(18)31912-6/fulltext

- American Journal of Obstetrics & Gynecology. (2019). Reducing primary cesarean delivery: Time to act. https://www.ajog.org/article/S0002-9378(18)32079-7/fulltext

- National Institutes of Health. (2019). Vaginal birth after cesarean delivery. https://www.nichd.nih.gov/health/topics/vbac/Pages/default.aspx

- World Health Organization. (2018). WHO recommendations: Intrapartum care for a positive childbirth experience. https://apps.who.int/iris/bitstream/handle/10665/260178/9789241550215-eng.pdf?sequence=1